Good where we’ve been, good where we’re going to. Good where we’ve been, good where we’re going to. — sung refrain, unknown author Dear Disciples, ‘Tis the season for end-of-the-year lists and resolution making for the new year to come. Spotify quantified my listening habits, with #SistersinLaw topping my podcast list and Engelbert Humperdinck crooning my most played song (A Man without Love, if you want to know. Thanks to Marvel’s Moon Knight TV series for the ear worm.) Barack Obama has published his popular Spotify music playlist, along with his favorite films and books of 2022. We love lists! There’s a list for most human endeavors: best film lists, top TV shows, biggest political stories, most influential people, and more. The Los Angeles Business Journal publishes a list of lists, a compilation of the lists published during the year. Perhaps it’s a way of closing the books on a previous year. We manage to get the last bits of the year stashed into a stuffed file folder, tucking it away and promising to look at it again soon. All the while we know once the file drawer is closed, time will slip by and the folder moved to the back of our memories. I am a sporadic list maker, returning to the practice when life’s details threaten to become unmanageable. Often lists are boring—the grocery list scribbled on the back of a receipt or a packing list for my suitcase. Sometimes lists are for a future dreaming—creating Pinterest boards of places to travel, restaurants to dine at, hikes to try. There is a poetry form of lists, and the first one I remember reading was Shel Silverstein’s marvelous poem, "Sick." In it little Peggy Ann McKay offers the reasons she cannot go to school that day, reciting an impressive list of her ailments: ..."I have the measles and the mumps, A gash, a rash and purple bumps. My mouth is wet, my throat is dry, I'm going blind in my right eye. My tonsils are as big as rocks, I've counted sixteen chicken pox And there's one more—that's seventeen, And don't you think my face looks green?... Have you made any lists for 2022? —moments of accomplishment, tasks left unfinished, or roads not taken? A compendium of joys or heavy griefs? Are you carrying into the new year a moving box filled with unnecessary regrets or grudges? What can you take with you into 2023 and what will you allow yourself to let go of? My favorite contemporary hymnwriter, John L. Bell, in the song, Take This Moment, uses the list poem form as a prayer to God for new beginnings. You can listen to the song on YouTube. Take this moment, sign and space; take my friends around; Here among us make the place where your love is found. Take the time to call my name; Take the time to mend Who I am and what I've been, all I've failed to tend. Take the tiredness of my days; Take my past regret, Letting your forgiveness touch all I can't forget. Take the little child in me scared of growing old; Help me here to find my worth made in God's own mould. Take my talents, take my skills; Take what's yet to be; Let my life be yours, and yet, let it still be me. —John L. Bell, (Take This Moment) Whatever lists we are carrying from this year to the next, may the grace of God always be our companion on the way.

0 Comments

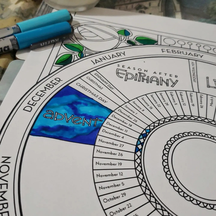

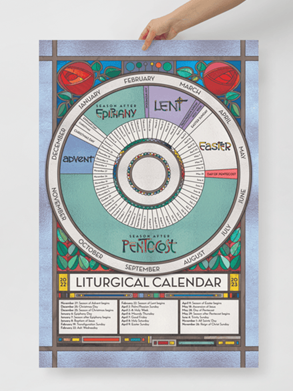

“LIKE A GREAT WATERWHEEL, THE LITURGICAL YEAR goes on relentlessly irrigating our souls, softening the ground of our hearts, nourishing the soil of our lives until the seed of the Word of God itself begins to grow in us, comes to fruit in us, ripens in us the spiritual journey of a lifetime.” —Joan Chittister The Liturgical Year: The Spiraling Adventure of the Spiritual Life As winter draws near, the nights grow longer and the hours of sunlight reach their shortest length of the year, we feel time in our bones. Often what we feel does not match the time on our clocks, when darkness falls so early. Surely it’s time to head to bed, we may think, only to check the clock and in shock discover it is only 6:30pm! (Or, maybe that’s just me!) We lean on our watches or phones to know the time, to help determine where we are in the movement of the day. The ancient Greeks had two words for time, chronos and kairos. Chronos is the kind of time we can quantify or measure, such as “The concert will last two hours” or “We averaged 65 mph on the way home.” Chronos is the time we see on our watches, the time we follow as we go to work or pick up the kids from school. We mark such time in minutes and hours, days, weeks, and years. The second word for time, kairos, concerns the meaningfulness of time, the potentiality of moments, expectancy of events. Kairos is the time of moments and breakthroughs, even interruptions. The church follows a calendar, with regular dates and festival times, which has points of connection with our chronos calendars. The new church year began on Sunday, November 27, with the first Sunday of Advent. There will be four Sundays of the season leading up to Christmas Day. Those dates are measurable, we can mark them on our personal calendars, keep track of those Sundays, note that Christmas Day is on a Sunday this year, too. Yet, the church’s liturgical calendar holds within it the possibilities of kairos time even as it marks the holy days of the Christian year. The church calendar invites us into an alternative plotline for our days, as it intentionally builds in times of preparation and repentance, with moments of remembrance and celebration. As Peter Leithart describes it, “the church calendar isn’t just a teaching device. It places us in the time of Jesus, and works the life and times of Jesus into us.” As we follow the rhythms of the liturgical year, we find a counterpoint to the secular calendar, a richer way of keeping time, walking alongside the stories of Jesus and diving deep into the ways of discipleship. This year we have liturgical calendar posters available for you. Take one home, put it up somewhere you can see it. Color the poster with your family. Explore the colors and the times of the church year and see how time changes and how keeping liturgical time may even change you. There is a kindness that dwells deep down in things; it presides everywhere, often in the places we least expect. The world can be harsh and negative, but if we remain generous and patient, kindness inevitably reveals itself. Something deep in the human soul seems to depend on the presence of kindness; something instinctive in us expects it, and once we sense it we are able to trust and open ourselves.

—John O’Donahue To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings There are times when I read John O’Donahue’s words on kindness and fear he is terribly mistaken. Stories of violence fill our airwaves; hateful words swirl in our society, wielded as weapons designed to silence and sideline others. We are days away from another election, and some elected officials and politicians shamelessly deploy racism and fear-mongering intending to motivate voters by their basest instincts. Ugly, fantastical rumors swell like wildfires, spreading across social media, while news on the very real challenges we face as a country suffer from lack of attention. At moments like these I tend toward despair, feeling deep down that the words of the poet Maggie Smith in her poem, “Good Bones,” may be more true than O’Donahue’s, ...Life is short and the world is at least half terrible, and for every kind stranger, there is one who would break you, though I keep this from my children…. And yet. Perhaps I am despite what I fear, surprisingly an optimist at heart, or merely naïve to a fault. Whenever I teeter on the abyss of despair, just when my cynicism thinks it’s won the day, something pulls me back. A fierce defiance rises up, just enough to push back against the forces of gloom. A spark of what might be hope appears, oftentimes in places I least expect to find encouragement. A few weeks ago I attended the 2nd annual Justice Festival at Morehead State University. Along with MSU students and staff, there was a class of high school students in attendance. Now, in the news you may read about the post-pandemic decline of test scores or in casual conversation it is often said that this generation is lazy and unengaged. The kids present at the Justice Festival upended those negative stereotypes. In workshops they asked insightful questions, brought facts to the conversations, and a tangible passion to issues which directly affect their lives. They were a real-life embodiment of the lyrics of the Broadway hit, Hamilton, “With every word, I drop knowledge. I'm a diamond in the rough, a shiny piece of coal.” Faced with the realities of injustice in the world, these high school students weren’t despairing; they were fired up and ready to rise up! As I left the Justice Festival, I realized that for all the helpful information presented, what I had really needed that day was the students from that high school class. In their passion I found an ember of resistance inside me, refusing to give up. I suspect Maggie Smith can’t quite let go of hope either, for her poem ends with a comparison to a realtor, walking prospective buyers through a fix-it-upper and the openness of a future yet to be, “This place could be beautiful, right? You could make this place beautiful. We could indeed make this place beautiful—one deviant act of kindness, one brave bit of good trouble at a time. May it be so. The founding of Morehead Normal School in 1887 grew out of the Rowan County feud. The State applied militia force to settle the problem, the Baptists held evangelistic meetings, and the Disciples of Christ established a school and a church.

—Morris L. Norfleet, Morehead State University Founding Years It reveals much about the Disciples’ spirit that our response to the chaos from a multi-year violent feud which left more than 21 people dead, destroyed thousands of dollars of property, and terrorized local residents of Rowan County was to send missionaries to found a school and organize a local church. William T. Withers, a prominent Lexington horse breeder, ex-Confederate colonel, and a former slave owner, underwrote the missionary endeavor. A young college graduate Frank Button and his mother Phoebe Button accepted the call from the Kentucky Christian Missionary Convention to come to Morehead. Their work was to establish a school in Morehead and to provide pastoral leadership for the Christian congregation. The early days were difficult. Later Wither’s daughter, Ida W. Harrison related the story that upon his arrival, Button was visiting with a man in town, “and while they were talking, firing began on the street, and they had to take refuge behind an old stone chimney, until the fusillade was over.” The school attracted early opposition from the community, perhaps a distrust of outsiders played a role. In a letter to Button in October 1887, Withers saw the controversy as an opportunity, writing, “Am not surprised at the opposition to your school. It was only what might have been expected—this very opposition will no doubt result in bringing your school before the public & that’s what you want.” Education and faith were bound together in those early years. In the same October letter, Withers expresses his pleasure in hearing of the progress in forming a congregation in Morehead and informs Button that a “nice plated communion service” was being sent from the deacons of the Main Street Christian Church in Lexington for use by the new Morehead congregation. The church, alongside Baptist, Presbyterians, and Methodists soon held its gatherings in the newly erected Union Church building, constructed in 1888 on the site which our church facilities now stand. Disciples’ influence continued in Morehead as the Kentucky Christian Missionary Society oversaw the mission of the Normal School for thirteen years, after which control of the school was transferred to the national Christian Women’s Board of Missions. The work of the school fit in with the larger mission of the Women’s Board of Missions, whose work encompassed educational and missional projects internationally and in the United States. Roy Roberson, minister of FCC Morehead from 1970 to 1984, speaking at the centennial celebration of Morehead State University, reflected on what he called the religious spirit of the time as a reaction to the social upheavals of the era which led to Frank Button’s move to Morehead said, “...this was an explosion that led to a birth of new religious thinking that combine religion with reason, faith with purpose, intellect with a desire to build a better world, the ability to think and apply that thinking to a faith perspective that would do something in the lives of others.” As we celebrate our 135th year as a congregation, once again we find ourselves in a time of uncertainty and upheaval. Rather than be reactionary, may we instead be moved to commit ourselves to a missional vision which faces the future with hope and steely determination. Let this be a time of celebration, a moment to look back, and an opportunity for a reclaiming of our congregational heritage, this rich legacy of faith and learning with which we have been entrusted.  And in this he showed me something small, no bigger than a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, as it seemed to me, and it was as round as a ball. I looked at it and thought: What can this be? I was amazed that it could last, for I thought that because of its littleness it would suddenly have fallen away into nothing. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and always will, because God loves it; and thus everything has being through the love of God. —Julian of Norwich, Showings As I sit down to write this column, the news is filled with scenes of the catastrophic flooding in Pakistan, with over 1,000 people dead, one-third of the country devastated, and thirty-three million people affected by floodwaters. High temperatures, warming oceans, and record rainfall contributed to this tragedy. Anjal Prakash, research director at the Indian School of Business in India’s Hyderabad and one of the lead authors of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, says “We have got to stop using the word unprecedented because every time a new precedent is being formed in South Asia. The impact of warming on Himalayan glaciers, which are retreating very fast, is much faster than we earlier thought.” (Chaudhary, Pakistan Flood, Aug. 29, 2022, Bloomberg) Here in Eastern Kentucky we have witnessed the horrors of flooding exacerbated by deforestation, mountain-top removal, and climate change. Had we heeded warnings from scientists dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, we might be in a different position in 2022. Had the church taken seriously our calling from God to be co-creators and stewards of the earth, the divides in popular opinions might not be so stark. But those decisions are in the past. This week the National Association of Evangelicals released an updated version of Loving the Least of These: Addressing a Changing Climate. The publication deftly connects the science of climate change with the biblical imperative to care for the poor. The president of the NAE, Dr. Walter Kim, explains the motivation behind the report, “Our concerns and motivations are not political. They are deeply rooted in the biblical conviction about God as Creator of this universe and humanity’s responsibilities to care for the gift of this creation,” he said. “As followers of Jesus, we certainly are committed to God’s glory that’s revealed in creation and the stewardship that would be our responsibility in caring for God’s artistry.” Data from the Pew Research Center reveals an unsettling generational divide on issues of addressing climate change, with younger folks, Millennials (born 1981-1996) and Generation Z (born after 1996) reporting higher levels of engagement and concern over climate change than older generations. The generations which are leaving or who have already left church are the ones with higher levels of concern for climate change. If they do look at what the church is doing on climate change, they seldom find faith communities publicly engaging environmental justice issues. This trend breaks my heart. When I was considering the call to the pastorate at FCC Morehead, the presence and activity of the church’s Creation Care team encouraged me. The commitment of individuals on that team and beyond remains a source of hope and encouragement. While the pandemic has hampered many initiatives, we have continued to prioritize our work to care for creation, particularly this Appalachian landscape on which we live, work, and play. For the third year FCC Morehead will observe the Season of Creation during September. The ecumenical celebration began in 2000 with the Uniting Church of Australia and has expanded across the globe. The observances differ from denomination and country, but remain rooted in the hope of restoration and jubilee for the Earth. This season is “a time to renew our relationship with our Creator and with all creation through repenting, repairing, and rejoicing together.” I hope you will find ways to join in the celebration and to take action to care for this amazing planet which has been entrusted to us by our Creator. Dear Friends,

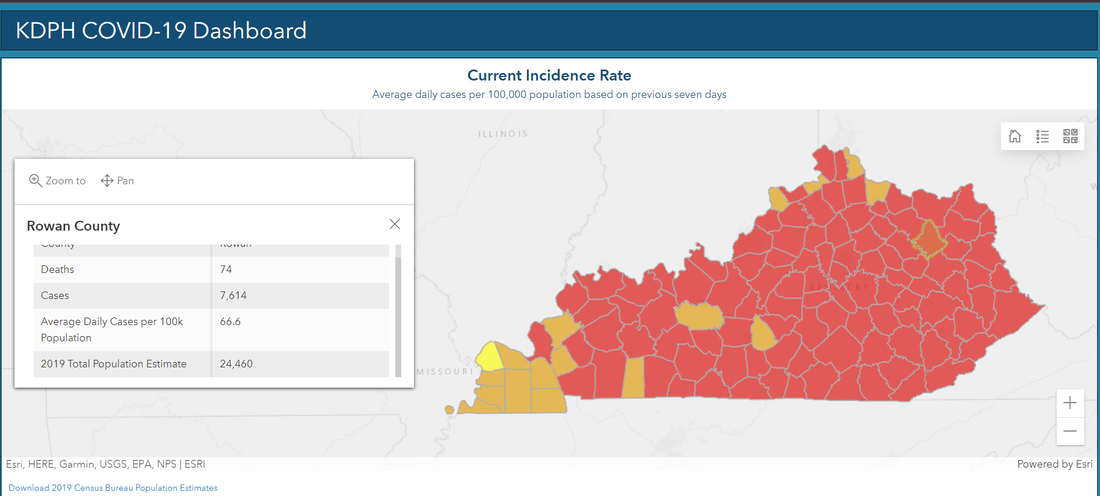

The Worship Safely Committee (Return to in person worship committee) met on Sunday, July 31, for a discussion about our in-person practices. The meeting was prompted by the ever-increasing number of COVID cases in our community and the upcoming return of Morehead State University and Rowan County students to the classroom. As we have seen this past month with both our pastor and our music director going through COVID, the virus is not negligible and causes a serious lack of productivity through sickness and the need to quarantine even when it is not severe enough for a hospital stay. The cognitive dissonance many of us are experiencing due to COVID fatigue is understandable. The current CDC recommendations are: "If you are in an area with a high COVID-19 Community Level and are ages 2 or older, wear a well-fitting mask indoors in public." We know this is right and true, but most of us are not currently masking when we go out of our house. We're tired of it. Again, understandably so. However, if we, as a congregation, are going to follow the CDC guidelines, which we committed to doing last year when this committee was formed. And, if we are going to try our darndest to love our neighbors as ourselves and protect them to the best of our ability, then we need to follow these guidelines. Even if it means that we're the only place in Morehead that is doing so. Even if it means we're irritated by it. Even if it means that we're a little uncomfortable in a hot mask in the dog days of summer. The committee is asking that you please wear a mask at church when we are there as a group on Sundays for worship starting on August 7 and continuing as long as Rowan County is in the red and cases are trending upwards. Thank you for your patience and your understanding as we continue to navigate this annoying, dangerous, and stubborn virus. Sincerely, Genny Jenkins, chairperson Nancy Gowler, minister  Charles Cousen after Myles Birket Foster, via Wikimedia Commons Charles Cousen after Myles Birket Foster, via Wikimedia Commons Once upon a time, it seems, we knew how to be ill. Now we have lost the art. Everyone, everywhere disapproves of being ill. Being ill is just not useful. The newspapers create a climate of guilt around it because of the time it takes away from useful, productive work….The stories make one feel that when ill you are somehow letting the side down, losing the nation money. Being ill is unpatriotic and terribly inconvenient to the work culture….It makes us feel guilty. —Tom Hodgkinson, How to Be Idle: A Loafer’s Manifesto I enjoy convalescence. It is the part that makes the illness worthwhile. —George Bernard Shaw It started with a tickle in the back of my throat and a stuffiness in my head. Perhaps summer allergies, I thought. Then the news came from a friend that they had tested positive for COVID, and we had visited with one another outside a few days earlier. My first at-home COVID-19 test was negative. Soon Ben was experiencing symptoms, too. Eventually home tests revealed what we’d already feared, after more than two years of avoiding COVID, vaccinated and with one booster, we were both sick. And unfortunately we were not alone. The newest variant of the virus has proved to be a potent strain, with numbers of infections on the rise in Rowan county and across the entire country. We chose to isolate until we had negative rapid tests, which took over a week. Luckily we were able to stay home and rest, treating our symptoms with over the counter medication. Even though we were isolating, we were not alone! Groceries were left on my front step. Care packages arrived on my back porch. Messages of support and prayers came from near and far. Genny Jenkins stepped in to help find folks to fill in for me in worship that first Sunday. Bob Pryor kindly agreed to preach and Alana Scott served at the communion table. In the office Barbara Marsh ably fielded extra duties, too. I am so very grateful to everyone who pitched in and for all the many kindnesses shared with us. Showing kindness to oneself often is a challenge in our society which prizes productivity and looks askance at idleness. Being ill is inconvenient. Just last week the president tested positive for COVID. Immediately videos, tweets, and announcements proclaimed we shouldn’t worry, he was hard at work. Powering through illness is often viewed as a virtue. Now that we’ve lived through 2 1/2 years of a global pandemic, I hope we’ve learned the hard lesson that when we’ve encouraged pushing through sickness often we’ve unwittingly exposed others to risk of disease as well. In his little book Recovery: The Lost Art of Convalescence, Dr. Gavin Francis shares wisdom he has learned over his years as a doctor treating patients on four continents. The word convalescence emerged in the 15th century, rooted in the Latin, meaning “to grow strong together.” Rather than “pushing through” symptoms, Dr. Francis argues that individuals recovering from prolonged symptoms embrace the concept of “pacing.” A healthy recovery involves developing the skills to recognize what our bodies are telling us, to “begin to slow down and stop an activity before they begin to exhaust their energies.” An April 2022 National Geographic article quotes Alba Miranda Azola, co-director of Johns Hopkins Post-Acute COVID-19 Program, “We have found that patients with post-viral fatigue that push through and enter a crash cycle have overall functional decline.” Indeed, the emerging advice for recovery reflects this reality: Stop, Rest, Pace. As I’m continuing my own recovery, I’m wondering if there is wisdom in the practice of convalescence for our congregations, too? After all, this pandemic has not only affected individuals but also changed our most beloved institutions. Rather than return to old habits and practices, can we learn the new skills of listening to our common life together? What is Spirit asking of us in this moment? What would it mean for us to “Stop, Rest, Pace”?  Thomas Jefferson's 1802 letter to Danbury Baptist Association Thomas Jefferson's 1802 letter to Danbury Baptist Association I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between church and State. —Thomas Jefferson in an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association, Connecticut Dear Disciples, As we approach July 4 with its celebration of the Declaration of Independence and the birth of our country, it’s fitting for Christians to reflect upon the role of religious liberty in our nation’s history and in our current day. The living out of the ideals of religious liberty has always been complicated and messy, as our country has wrestled with adjudicating among competing interests. Democracy is hard work, after all. Despite protests to the contrary in certain vocal Christian circles, the idea of the separation of church and state does not sideline people of faith. The first amendment offers protection for religious communities from interference from the secular state, regardless of their position of influence in our larger society. The flip side of that protection is equally vital—religious communities are restrained from imposing particular religious views onto society at large. When one particular religious institution aligns itself with government power in order to legislate its particular worldview onto others, our rights to religious liberty are diminished. One of the rallying mottos long embraced by the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is “In essentials unity, in non-essentials liberty, in all things charity.” The maxim predates our founding as a denomination, first appearing in Lutheran and German Reformed churches in the 17th century. While not unique to Disciples the motto has been a distinctive of our religious identity, affirming together that “Jesus is the Christ,” and also embracing individual discernment of matters of faith and morality. Disciples recognize that people of faith will have varying views on ethical issues, and we have long struggled to live out that commitment to diversity of belief while maintaining a welcoming faith community and living out our understanding of God’s call to justice. Among several recent troubling rulings from the Supreme Court is the opinion in Kennedy v. Bremerton, which upends protections for public school students from teacher-led religious practices. A Christian high school football coach regularly offered prayer in the middle of the football field immediately following games and also gave Christianity-laced motivational talks in the locker room. Apprised of his actions the school administration told the coach he could pray privately, but he could not lead students in prayer while he was on the job. They offered accommodations so that the coach might continue his private prayers in a less conspicuous place. Let me be clear: the coach could have prayed on the sidelines, privately in the press box, in his car on the way home, and in any number of other places. Instead, after finding legal backers who were looking for a Supreme Court fight, the coach resumed praying on the field at the 50 yard line. He was subsequently fired. At issue was not the coach’s freedom to practice his faith through personal prayer at his place of employment, but rather his performance of a religious act in such a way that students, players, or staff might feel pressured into participation. This Supreme Court decision seriously weakens the rights of families to raise their children according to their own religious or secular traditions. As people of faith who hold to the idea of personal liberty with respect to religious practices, this decision by the court should trouble us. Alexander Campbell would write in his memoirs that the United States was “a country happily exempted from the baneful influence of a civil establishment of any peculiar form of Christianity, and from under the direct influence of an anti-Christian hierarchy." I fear we have entered a time in which such dedication to religious liberty for all no longer holds sway. Inspired by love and anger, disturbed by need and pain,

informed of God’s own bias, we ask him once again, “How long must some folk suffer? How long can few folk mind? How long dare vain self-int’rest turn prayer and pity blind?” —John L. Bell (listen to the hymn) These are difficult days to find hope. Our news is filled with stories of war and aggression with millions of refugees fleeing their homelands. We’ve been shocked by mass shootings in which young children are murdered in their classrooms and grandmothers and fathers are gunned down in grocery store aisles. In conversation after conversation I’ve had over the past two weeks, common threads of anger and hopelessness are woven together along with a profound sense of helplessness. We’ve been here before. As the years go by, more of us have tragic stories to tell. I was living in Oregon in 1998 when a 15 year old boy murdered his parents and then went to his high school cafeteria in our community and shot 50 rounds of ammunition, wounding 24 and killing two students. This was one year before the shocking attack at Columbine High School in Colorado. How do we respond to these days in faithfulness and with hope?

Let us not lose heart. The gift of life is precious, fragile, and holy. Let us tend to the sacred in our world with hope and courage.  As long as we live, there is never enough singing. —Martin Luther Dear Disciples, One of the gifts of returning to in-person worship has been the return of the choir in our sanctuary. I grew up in a singing congregation, with children, youth, men’s, and chancel choirs. We were a singing bunch! The congregation in Centralia, Illinois, had two morning worship services. The chancel choir sang in the second service, and there was no special music in the first service held at 8:15am. Imagine then how important music was to our high school youth group, that for two years on our own we organized and offered special music for that early service—teenagers practicing during the week and then getting up early on Sunday mornings to sing! Research on choral music groups suggests that singing together has positive impacts on an individual, finding improvements in mood, reduced stress and anxiety, and greater subjective well-being. While the exact connections between choral singing and individual well-being are not known, I do know that the experience of creating music together with others is an exhilarating one. Something amazing happens when disparate voices come together, listening to one another, balancing and blending together, making wonderful harmonies. Drop by the sanctuary on Wednesday evenings and you will find our choir practicing with intention and with a healthy dose of good humor. Yes, laughter is an integral part of our rehearsals! As our choirs heads into their final weeks before summer break, I want to offer my heartfelt thanks to all of the wonderful musicians who have brought their gifts to our worship. Our music director, Genny Jenkins, is a vibrant and passionate leader, who brings out the best in singers and musicians. Our musical interns from MSU have been such a joy to work with. A huge shout-out and thank you to Caleb Fouts, Anna Grayson, Maura McCoy, Everett Quiggins, and Katie Webb. We’ve been blessed by their musical talents and by their active participation in our congregational life. And I want to offer a word of thanks to our keyboardist Isaiah Florence. He has such a beautiful style of playing the piano, and if you’re in the sanctuary before worship you may have heard his jazz improvisations, too. While church music is a new area for him, we are grateful for his talents. I’m also so very grateful for our congregational members who make up our chancel choir and our bell choir. It’s an act of love and dedication to attend weekly rehearsals and to offer musical leadership in worship on Sundays—I hope you’ll join me in offering your word of thanks to members of our choirs. |

AuthorA native of Illinois, Rev. Nancy Gowler lived for 26 years in the Pacific Northwest. She joined the ministry of First Christian Church in Morehead, KY, in July of 2020. Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed